A Casual Civilian vs. Improviser Conversation

Improviser: Many improvisers LOVE form.

Civilian: What? Wait. Isn’t form planning?

Improviser: Yes, in some ways it is.

Civilian: But, hold on, you do improv. Shouldn’t you guys make everything up?

Improviser: We do but the form sets us up to be free from planning.

Civilian: What???

What is Form?

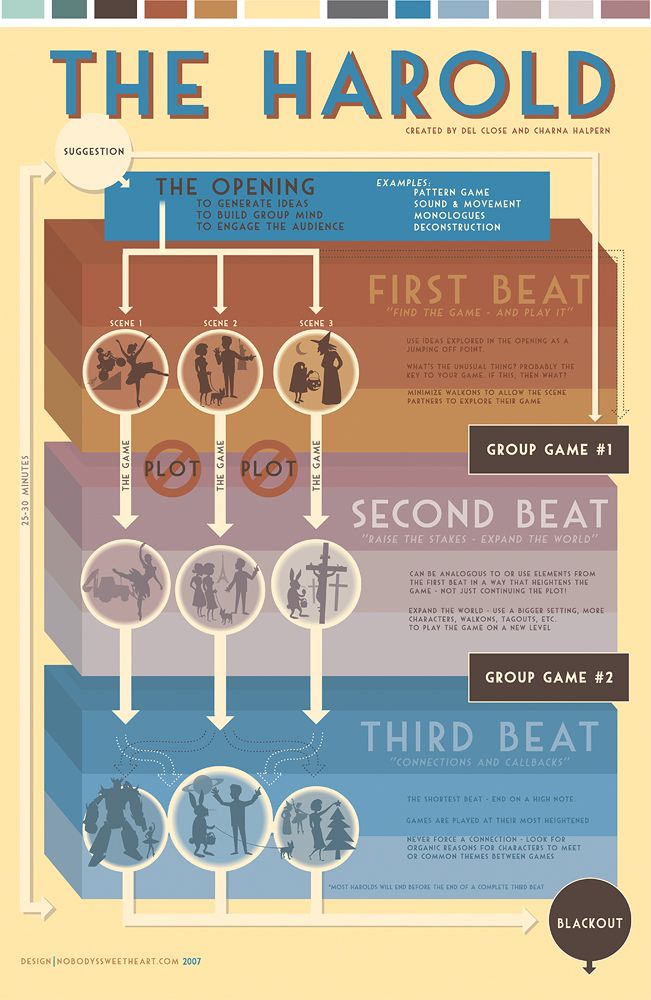

Having a form in improv is simply an agreement made by the actors involved in a piece agreeing to how the improvisation will be presented for an audience. This ranges from executing the beloved Harold all the way down to doing a simple improv game of Sit, Stand, Lean. The actors agree that they will improvise within a series of guidelines as the night progresses.

Having a form in improv is simply an agreement made by the actors involved in a piece agreeing to how the improvisation will be presented for an audience. This ranges from executing the beloved Harold all the way down to doing a simple improv game of Sit, Stand, Lean. The actors agree that they will improvise within a series of guidelines as the night progresses.

One common phenomenon that happens when playing with form is that the actors’ scene work seems to be more guarded and lackluster once they begin improvising within a form.

Playing For The Form vs. The Scene

When starting a form for the first time, actors tend to want to nail the form as planned. I mean, why have a form if you’re not going to do it, right? They start out finding that the form is useful, helpful, and requires less thinking in general – at first. A ton of ideas spring forth in their minds, they try new characters, scenarios, games, and concepts. They feel supported in their scene work by having a form they can always rely on to get them to the next series of scenes.

Then once they get married to the idea of doing the form, they begin to measure the overall piece by whether or not each part of the form was accomplished. The actors begin to get in their heads about the form itself because they want to make sure they rock that form; if things stray from that form, then they get lost trying to figure out how to get back on track. The scenes then are pushed and pulled in a manner so that they can accomplish the form. All the while they’re playing desperately to get it right, the scene work suffers all along because they’ve already collectively planned what the scenes are about and that’s paramount to everything else. They then feel trapped by the form and begin to lose interest in it; they begin blaming the form for the reason they feel unsatisfied with their work; some quit improv as a result (just in extreme cases 😉 ).

Take for instance The Harold: How many times have you seen a Harold done perfectly while being completely entertaining? Exactly. Rarely. I’m not saying it’s impossible or there aren’t improv teams out there doing them consistently and doing them well; however, I have yet to see a perfect Harold that I really enjoyed. When the actors go out there and play what’s in front them and use the Harold for structure, they’re typically enjoyable shows. When they play to get through the Harold, the shows very clunky; there are weird scenes that make no sense thrown into the show or they destroy the momentum of a previous scene by inorganically throwing in a game to follow it or do unnecessary asides. The inorganic nature of playing for getting through a form is what really makes the experience miserable for those playing and those watching.

Take for instance The Harold: How many times have you seen a Harold done perfectly while being completely entertaining? Exactly. Rarely. I’m not saying it’s impossible or there aren’t improv teams out there doing them consistently and doing them well; however, I have yet to see a perfect Harold that I really enjoyed. When the actors go out there and play what’s in front them and use the Harold for structure, they’re typically enjoyable shows. When they play to get through the Harold, the shows very clunky; there are weird scenes that make no sense thrown into the show or they destroy the momentum of a previous scene by inorganically throwing in a game to follow it or do unnecessary asides. The inorganic nature of playing for getting through a form is what really makes the experience miserable for those playing and those watching.

The form is there to serve one purpose – to give the actors playing it a direction – a suggestion – as to what kinds of scenes should come up next; however, if the scenes don’t go down that road, DON’T FORCE IT! There are many roads to an end; give yourself the freedom to travel unfamiliar roads when improvising a form. Think about how many times you’ve traveled home from a show or rehearsal. There are many ways to get home but there are better ways of achieving the same goal. You may have to take detours along the way to avoid construction, road closures, and annoying traffic, right? Well, that’s what we’re doing with the form – taking our usual route home but always keeping in mind we may need to leave it when circumstances require it.

Remember, the form is there to guide not bind.

Play For The Scene

Instead of worrying about the form, concern yourself with the characters on stage. When you’re on the backline, think about where you are in the form and use that to inspire you to play what is going on in front of you. If you know that the form requires three scenes where we learn the backstory about the protagonist, ask yourself, “What kinds of characters are in the same reality as the protag and why do they care about them?” You don’t have to be able to answer all of this off the backline but rather have this mindset of answering those questions as you go out. Deal with the reality set forth in this slice-of-life moment and don’t worry about it “making sense” in the story. The story will be the sum of the parts you put forth in these multiple scenes/games.

Instead of worrying about the form, concern yourself with the characters on stage. When you’re on the backline, think about where you are in the form and use that to inspire you to play what is going on in front of you. If you know that the form requires three scenes where we learn the backstory about the protagonist, ask yourself, “What kinds of characters are in the same reality as the protag and why do they care about them?” You don’t have to be able to answer all of this off the backline but rather have this mindset of answering those questions as you go out. Deal with the reality set forth in this slice-of-life moment and don’t worry about it “making sense” in the story. The story will be the sum of the parts you put forth in these multiple scenes/games.

I tell my teams to let the audience make the story for them. Audiences are smart and dumb. They’re dumb in the sense that they may not recognize the techniques being used on stage to provide them entertainment, but they’re smart in that they can put together sequences of scenes to make a story out of a bunch of disjointed scenes. The better you can play so that what’s going on between scenes to make sense to an audience member, the more you’ll be perceived as a good team. If you can’t do that, don’t worry about it. The audience wants you to succeed. They’ll make a story up for you even if you don’t have one.

Just Do Good Work

As Michael Gellman says, “Good theatre is good theatre is good theatre” – just do really good scenes and the audience will love it even if a story or form isn’t adhered to. Having a form is a double-edges sword for most improv groups. Use it to guide your work but don’t be afraid to abandon it to achieve better scenes.